Debt Creates Money; Where Does it Go? Part 2

What happens to the money created by debt in the US?

January 25, 2021

Estimated read time: 16 minutes

Prologue

Federal Debt

Municipal Debt

Financial Industry Debt

Corporate Business Debt

Non-Corporate Business Debt

Consumer Debt

Conclusion

Prologue

$109 trillion of debt. Over $3 trillion in interest a year.

In last week’s article we covered how and why the United States creates money through debt, but we didn’t explain the full consequences of a debt-based system.

Accounting for these consequences requires simplifying assumptions. The Federal Reserve’s tracking of US balance sheets contains hundreds of thousands of data points and doesn’t even scratch the surface of how the money actually flows to and from different accounts. Doing so would require accurately tracking every single unit of currency, inside and outside of the USA, which we simply lack the transparency to achieve.

So instead we’ll focus as much as possible on just the debt. What happens with the money that we create through debt. Specifically:

Who is responsible for paying back the debt?

What does the interest look like?

Who receives the money created by debt?

Who owns the debt?

We’ll ask these four questions across 6 major types of debt that account for almost all of the debt in the USA. Furthermore, we will talk about total outstanding debt, rather than the amount of new debt per year.

This article is going to be very data heavy. I believe this is necessary to tell the complex story of the impact of our debt-based economy. But to keep this grounded in context, I’ll restate the reason why the US is founded in debt that was mentioned in last week’s article.

We have a growing number of people with increasing and changing desires. In order for this growing population to be able to receive a paycheck that grows every year instead of shrinks, we need to increase the amount of money in the world. But simply printing money risks hyper-inflation, where your net worth can, in the span of a month, lose value to a microscopic fraction of a penny of its original value. So debt seemed to solve the problem of creating money without triggering inflation.

However, what are the costs of using debt?

Federal Debt ($27.6T)

SUMMARY:

Discussing the Federal Government’s debt is a good time to bring up the difference between deficit and debt. Deficit is how much money a government spends every year minus how much it earns. Debt is the sum of that overspending.

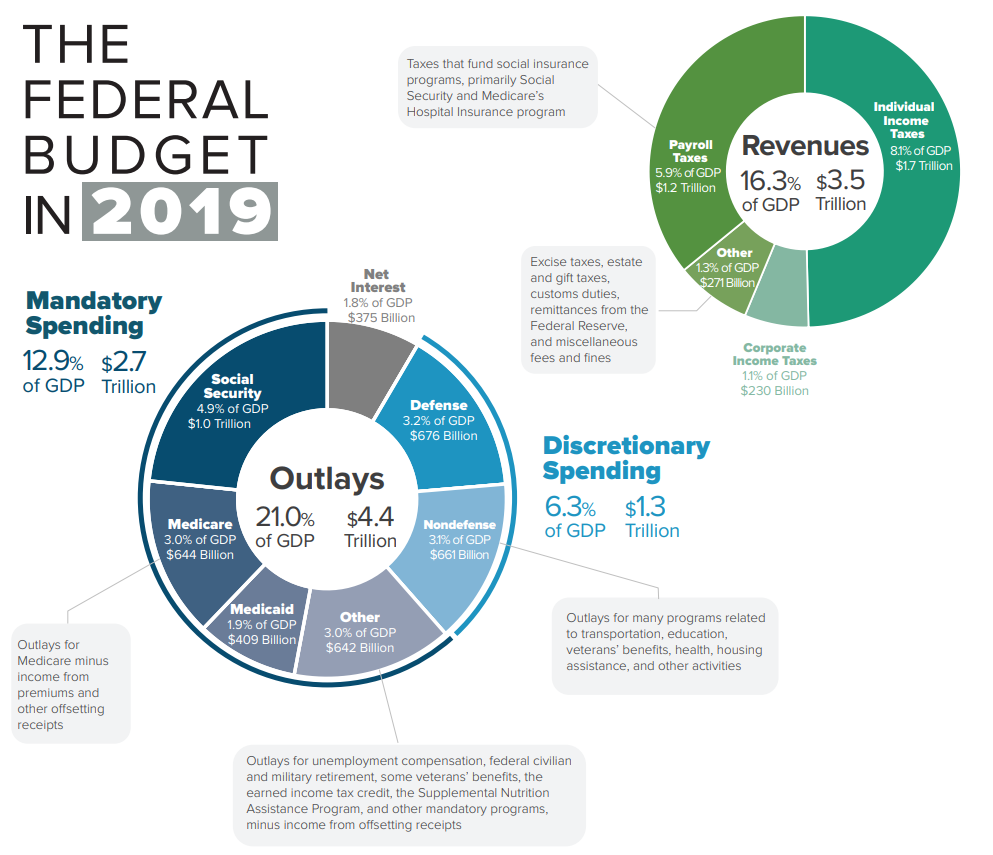

Given that, analyzing how the annual budget has been spent effectively describes where the money from the debt has flowed. As the numbers below show, a large amount of that money is concentrated in a small fraction of America. Specifically, between social security, Medicare, Medicaid, and defense spending, 67% of Federal spending goes to 33% of the country ($18T to 107.25M, $168,000 per person). 33% of the money is spread between 67% ($9.1T to 220M, $41,000 per person).

THE FOUR QUESTIONS:

Who is responsible for paying back the debt?

48.5% income tax (124M 49% of adults)

34% payroll tax (32.5M businesses + 124M 49% of adults)

6.5% corporate income tax (1.6M businesses, most businesses aren’t corporations)

7.7% from excise/estates/gift taxes and Federal Reserve profits

What does the interest look like? The range is 0-4.5%, depending on when the debt was sold and how long its maturity length is.

Who receives the money created by debt? Because federal money goes to children as well as adults, we’ll be calculating the percentage of the total number of Americans instead of just adults.

22.7% spent on social security, minimum age for receipt is 62 (46M, 14% of all Americans)

14.5% spent on Medicare, minimum age for receipt is 65 (41M, 12.4% of all Americans)

14.5% spent on Medicaid (72.5M, 22% of all Americans)

15.3% is spent on defense. For some rough estimates, the Department of Defense has 1.3M members and if you combine the employees of the top ten defense contractors you get roughly another million. So we could make a rough estimate of 2.3-3 million .09%

1.8% paid to debt holders

Remaining 29.5% broadly spread beyond that (top 3 are health/human services, education, and veterans affairs)

29.3% foreign investors

32.5% US Investors

11.2% Federal Reserve

27% US Government (social security and pension funds)

Municipal Debt ($3.8T)

SUMMARY:

Municipal Debt can be thought of in similar terms to Federal Debt. Instead of debt taken on by the federal government, municipal debt is taken on by states, cities, and counties. However, municipal debt is not nearly as transparently tracked as federal debt, so we will have to make more assumptions.

Municipal debt funds services like public schools, maintenance of public property, and public transportation. Unlike almost every other form of debt, any money paid as interest by municipal bonds is untaxed. That may go toward explaining why households and nonprofits own and receive interest from 46% of all municipal debt, more than any other type of debt.

Around 16 million Americans are directly employed by State and Local governments, so if we were to assume the debt money flowed to them, then we have $3.8T to 16M, $237,500 per person.

THE FOUR QUESTIONS:

Who is responsible for paying back the debt? State/city/county governments

What does the interest look like? We can only estimate, because this market isn’t the most transparent

Who receives the money created by debt? As an example, we’ll use California’s state budget.

47% Education (4M, 1.6% of adults)

33% Health and human services (18M, 7% of adults)

8% Corrections and rehabilitation (462,300, .2% of adults)

12% Other (includes transportation and environmental protection, but hard to say total number)

46% Individual households and nonprofits

46% Financial Institutions

8% Other

Financial Industry Debt ($50T)

SUMMARY:

The Financial Industry’s debt is the least transparent of all. We can make almost no assumptions. In fact, after the Financial Crisis, the Federal Reserve heavily criticized banks for not publicly accounting for a massive amount of debt. Constraints have been placed on banks since then, but we still lack full transparency.

We do know the amount of people who work in finance. Roughly 6.3M (1.9% of adults) work in finance, while companies owned by financial firms (specifically called Private Equity firms) employ 11.3 million (3.4%).

We also know rough estimates on the amount of Financial Debt from the Federal Reserve’s accounting in 2017, which is how we come to $50T. But beyond that, it’s difficult to make even the roughest of estimates.

THE FOUR QUESTIONS:

Who is responsible for paying back the debt? American Banks

What does the interest look like? Almost impossible to say.

Who receives the money created by debt? We can only assume financial institutions (in and out of America)

Who owns the debt? We can only assume financial institutions (in and out of America)

Corporate Business Debt ($10 Trillion)

SUMMARY:

Corporate debt is at the same time transparent and opaque. It’s extremely transparent in how much there is and the general interest rates. Corporate debt is graded from AAA “high quality” debt, to CCC or below “low quality” debt. In general the higher the quality, the more likely the debt is to be paid back, the lower the interest rate.

Where corporate debt becomes opaque is in regards to how it’s spent. For many public companies the only accounting visible to the public is the balance sheet, which only really gives X dollars were spent and Y dollars were made. A breakdown of X and Y, how money was specifically spent or specifically made, does not generally exist. So in regards to how money is spent, we will have to make very aggressive assumptions.

Assumptions like Amazon’s business is representative of all US corporations. Assumptions like the way all money spent by corporations is how debt is specifically spent. These assumptions are flawed, but we need assumptions like this to get a general ballpark estimate.

Using these assumptions, we approximate that 29% of spending is on employees (as justified below), 69.5% is on other businesses, domestic and foreign. Effectively, $2.1T of corporate debt is spent on employees totaling $8,200 per adult.

THE FOUR QUESTIONS:

Who is responsible for paying back the debt? Corporations (think more office buildings less local bar)

What does the interest look like?

AAA (current 1.72%, long term average 4.12%) ($.071T, .7% of total)

AA (current 1.54%, long term average 4.17%) ($.525T, 5.2% of total)

A (current 1.65%, long term average 4.61%) ($2.63T, 25.7%)

BBB (current 2.17%, long term average 5.38%) ($3.98T 39.1%)

BB (current 3.57%, long term average 6.87%) ($1.37T, 13.5%)

B (current 4.63%, long term average 8.68%) ($1.29T, 12.6%)

CCC (current 8.19%, long term average 14.52%) ($.332T 3.3%)

Who receives the money created by debt? There is no easy way to say how debt is spent at one company, let alone every company. As a grossly simplified example, we will use the way Amazon spends money.

Amazon spent $270B total in 2019

$4B, 1.5% was spent on taxes and interest

To estimate the amount spent on employees: Amazon has 1,000,000 US employees,350,000 warehouse employees are paid $35,000 a year, and we might roughly assume the rest to average $100,000. With this rough assumption we see $77.3B (29%) spent on labor, with the remainder paid to other companies.

27% Foreign investors

8% Households/nonprofits

11% Pension funds

45% Financial institutions

10% Other

Non-Corporate Business Debt ($3.8 Trillion)

SUMMARY:

Non-corporate debt is very similar to corporate debt. It’s debt taken out for businesses that don't have clear public documentation of spending. But because these loans aren’t publicly traded, we only have transparency on interest rates for SBA loans. Furthermore, non-corporate businesses are typically smaller mom and pop businesses whose debts come through SBA loans.

If we make roughly the same assumption as with corporate debt, then effectively $798B of non-corporate business debt is spent on employees totaling $3,100 per adult.

THE FOUR QUESTIONS:

Who is responsible for paying back the debt? Typically, you would assume small businesses. However, it’s worth noting that most of Koch Industries’ companies are non-corporate businesses and they pull in $115B in yearly revenue.

What does the interest look like? 5.5-8% if SBA loans. Otherwise expect something similar to corporate business debt.

Who receives the money created by debt? If we make similar assumptions as before, again because lack of transparency, 29% employees, 1.5% taxes and interest, 69.5% to other businesses

Who owns the debt? It’s hard to say because of the lack of transparency, but at least for SBA loans, expect banks and credit unions.

Consumer Debt ($14 Trillion)

SUMMARY:

We end with consumer debt because it is the debt most people are familiar with. You are a consumer so, if you’ve ever borrowed money, you held consumer debt. Consumer debt is different from the other 5 categories because of how neatly it can be broken further into sub-categories. It also has some of the most available information, so the estimates will be most accurate here.

If we assume the average interest rate for every type of debt, then the average American is $55,000 in debt with 9.3% APR.

But averages can be deceiving. If one person makes $0 and another person makes $100, the average is $50, but only focusing on that average completely misses the disparity in money made.

To dig beyond the average, it’s worth noting that, despite mortgages taking up 73% of total consumer debt, only 63% of adults own their homes. And with property debt, unlike the other forms of consumer debt, you largely pay yourself, with only the interest being paid to others. In effect, only 5% of $10.8T is paid to others, or $3,400 per homeowner per year.

On the other side of the coin, people who haven’t purchased homes typically have worse credit scores, which means they pay more in interest on the rest of their debt. If we make the rough assumption that the non-property consumer debt is evenly split between all adults, then the average non-property owner is $34,000 in debt at 17.3 % APR. And all of this money, the $5,900 yearly interest payments and the $34,000 in principal, is all owed to other people.

Mortgage/HELOC ($10.8 Trillion)

SUMMARY:

A mortgage, as most people know, is debt taken on to purchase a house. Home Equity Lines of Credit are loans you can take out once you have already purchased the house, that typically have lower interest rates than other types of loans since they are backed by property.

THE FOUR QUESTIONS:

Who is responsible for paying back the debt? 63% of American adults. It’s worth noting though, that home ownership for those aged 35 and under is 36.4%, while 70% of those 45 and over own homes.

What does the interest look like? If you have good credit, you can expect interest rates of 3-7% depending on credit score and year. If your credit score is 640 or less, the interest rate will almost certainly be variable (changes year to year) and can span from 8-20%. When I mentioned in last week’s article how interest rates multiplied overnight during the housing crisis, I was describing these variable interest rate mortgages offered to those with low credit scores.

Who receives the money created by debt? The former homeowner receives the money created by the debt, but you pay yourself as you work to pay off the principal of the debt. Every dollar you pay to the principal is a dollar you get back if you were to sell your house.

Who owns the debt? This info is not transparent as anyone who saw The Big Short can attest; however, we do have some insights and can make assumptions from there. The Federal Reserve holds $2T or 18.5% of mortgage-related debt. This means that the US Financial Industry holds at most $8.8T or 81.5% of mortgage-related debt, though some may be owned by foreign investors.

Other ($420 Billion)

SUMMARY:

The Federal Reserve’s notes on “other” were not specified in the documents I found, so we will focus on a snapshot of an example and make some extrapolating assumptions. As a specific example, we will focus on payday loans.

The Four Questions:

Who is responsible for paying back the debt? At a minimum 12M (6.4% of adults)

What does the interest look like? 150%-650% APR

Who receives the money created by debt? Businesses receive the upfront cash, payday loan companies receive the principal repayments.

Who owns the debt? Payday loan companies

Credit Cards ($840 Billion)

SUMMARY:

Credit cards have interest rates that are higher than almost every other form of debt, consumer or not. In large part that’s because they, like payday loans, typically are backed by nothing. A mortgage is backed by a house, an auto loan is backed by a car, but credit cards are backed by nothing.

THE FOUR QUESTIONS:

Who is responsible for paying back the debt? 120M (64% of adults)

What does the interest look like? The average is 12-19%, highs can get over 25%.

Who receives the money created by debt? Businesses.

Who owns the debt?

$90B or 11% in credit card debt is retail cards, so the debt is held by retail businesses (think Macy’s or Express)

$750B or 89% (the remainder) is held by the the Financial Industry

Auto Loan ($1.2 Trillion)

SUMMARY:

Auto loans are similar to home loans in that you are buying something with resale value, a car. However, unlike most homes, cars lose significant value over time. If you buy new, cars lose 60% of their value in 5 years. As you might expect, this leads auto loan interest rates to be higher than mortgages.

THE FOUR QUESTIONS:

Who is responsible for paying back the debt?108M (42% of adults)

What does the interest look like? 3-10% depending on credit score and year. For reference, if your credit score is over 720, expect 3.6% APR. If your credit score is less than 689 (in 2020, the average credit score for those under 39 years old is 680), then expect 7.02% APR.

Who receives the money created by debt? Car companies, who employ 1.7M people, receive the upfront payment, but when you pay back the principal you receive a small amount of your original money in auto resale value.

66% Financial Institutions

34% The Car Manufacturer or Dealer

Student Loans ($1.54 Trillion)

SUMMARY:

The argument for student loans is that they are supposed to be investments in your future. That you earn more after college. And it’s true that the median salary of a person with a bachelor degree is $44,000, while the median earning of somebody with a high school diploma is $30,000. But when you take into account that people with high school diplomas work during the four years university students are in college, as well as take into account student debt, then you realize that it takes 8 years out of college for a person with a bachelor’s degree to out earn the money earned with a high school diploma.

Moreover student loans are intended to be paid off in 10 years. In reality, the average time until debt payoff is 21 years.

THE FOUR QUESTIONS:

Who is responsible for paying back the debt?45M (17.6% of adults)

What does the interest look like? If the loan is Federal, 2.75% -7% depending on year, amount, and whether the student is undergrad or grad. Also, federal student loans are capped at $23K subsidized (cheaper), $57.5K total. If the loan is private, 4-12% depending on credit score and whether or not a cosigner is used. The difference between with/without a cosigner can be up to 4% points.

Who receives the money created by debt? The money is paid to universities but there isn’t a lot of transparency on how universities spend their money. A fraction goes to the 3.6M University employees. Some money is spent on construction/repairs (the total amount of construction employees is 11.2M). Some money goes to student aid (again 45M students). The rest goes into endowments. Worth noting, over a 24-year period (1986-2008), endowment size grew by nearly 800% while university costs grew by only 300%.

Who owns the debt? US Gov (92%) + the Financial Industry (7.9%)

Conclusion

Debt is a solution to an economic problem. Debt forms the basis of a system wherein we can print money as needed, but the interest rates mean the money is created ideally only as needed. This system requires new debt to be taken out by future generations to pay existing debt, but if not enough new debt can be taken out or too much new debt is required in too short of a time, then we risk significant defaulting on payments. And with all of the accounting we’ve just done, we now have the numbers to roughly verify how well this system is working out.

If we were to assume that all Federal and Municipal debt is spent on consumers, then the max amount of money given to consumers through debt is $41.5T. Meanwhile, consumers pay $1.8T in interest a year. With these numbers, it would take 34.7 years for the consumer debt interest to eat through all of the money given to consumers that was created by debt.

At first glance, this might make it look like our debt-based system is working perfectly.

But if you’re not part of the 33% of the population that’s over 62, paid through defense spending, or on Medicaid, the total money given to the remaining consumers drops to $26.9T and 34.7 years drops to 20.7 years. If you also aren’t one of the 63% of adults who are homeowners, that total drops to $16.8T and 20.7 years drops to 12.9 years.

If we were to take an admittedly extreme example and imagine this system without any government assistance, then those without homes would only be receiving the $2.9T from businesses. With this, in 1.6 years all of the money these consumers received that was created by debt would be eaten by consumer debt interest.

Meanwhile businesses pay $580B in interest a year, and have received a total of $11.46T in money created through debt. With this total, it would take 19.8 years for the business debt interest to eat through all of the money given to businesses that was created by debt.

This is rationally justified. Interest rates are typically indicative of risk. When a bank loans somebody money, there is always the risk that the person or business defaults and the bank loses all of the loaned money. Interest rates are supposed to balance out the risk. The less likely a debt is to be repaid, the higher the interest rate.

Businesses typically utilize debt to grow their business and make more money, so these loans can be seen as less risky and justify a lower interest rate. Consumers, when not purchasing homes, typically utilize debt in ways that spend money on goods/services rather than investments, so this debt is seen as more risky and justified a higher interest rate.

This is rational. And this is crippling. We’ve become reliant on government debt to prevent consumers from bleeding out and that still leaves gaps where over 30% of Americans can slip through the cracks.

In such a situation, what is a consumer supposed to do? What is a human supposed to do?

To be answered in part 3.

Holy-Moly! That WAS data rich! Jordan, is this series part of any coursework for you? If not, can you publish, aside from this blog? Thank you ~

Effective and powerful conclusion. And great hook for next week as well.